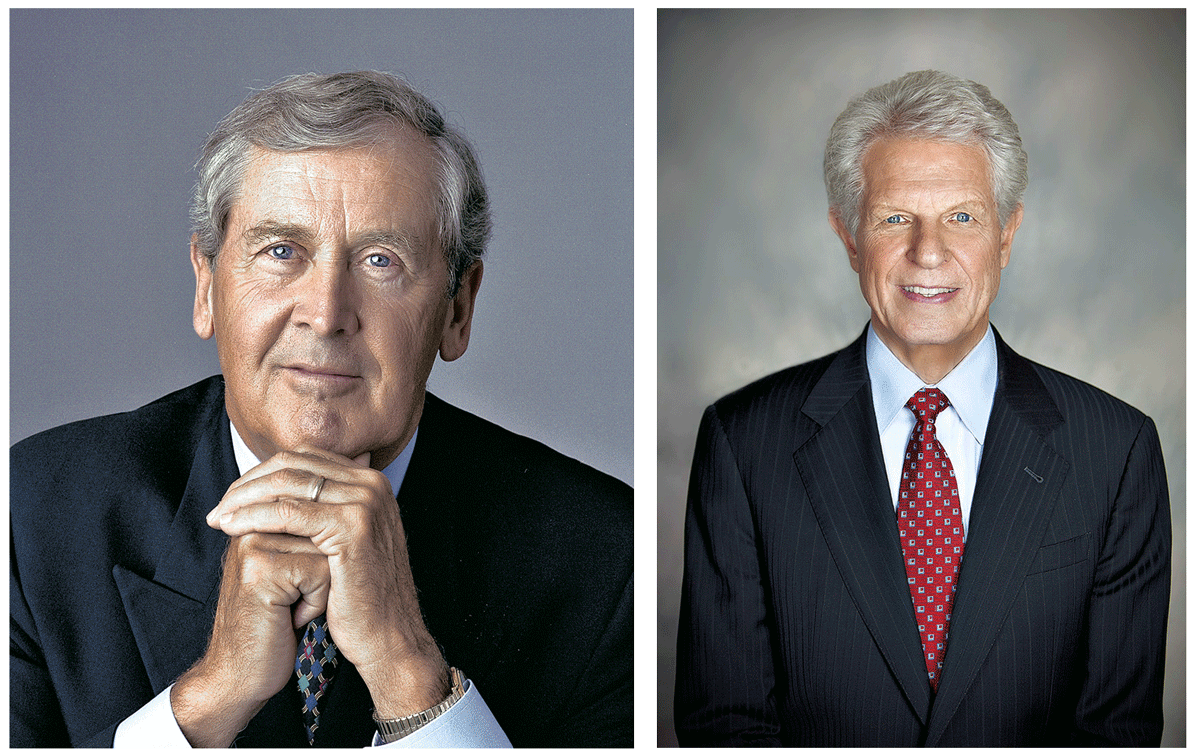

Recently, the research and marketing community quietly lost one of its brightest, most innovative thinkers and practitioners.

Kevin Clancy was a pioneering giant. One of only two ‘three-fers’ ever, as I term it: Market Research Council’s Hall of Fame, 2008. ARF’s Great Mind Award, 2012. AMA’s Charles Coolidge Parlin Award, 2015. Of the few people who have meant a lot to my career over the years, Kevin’s influence was the greatest and most meaningful. I joined Yankelovich specifically to work with and learn from Kevin. I continue to think in the ways that Kevin taught me about positioning, pricing, segmentation, and forecasting. Kevin was a brilliant communicator, especially of complicated ideas, and I still borrow from the things I watched him do in front of a room. Especially his tongue-in-cheek humor. He mentored many of us, and as word of his passing has gotten out, the accolades and grateful memories have been pouring in on social media and text threads. His professional legacy is enormous.

So, today, I want to share three important lessons—overarching ones—that I learned from Kevin, with a bit of Kevin’s story tied to each.

Marketing Intelligence. This was the tagline for Yankelovich Clancy Shulman when I joined in 1991. The firm was a few years out from the merger of Yankelovich, Skelly & White and Clancy Shulman Associates. Many YSW people had left, so Kevin and his partner Robert Shulman were rebuilding the business with new people and new methodologies, a shift to what Kevin liked to say was “state-of-the-science modeling.”

Kevin began his professional career at BBDO in 1966 as one of a power trio of associate research directors. Kevin himself. Larry Light, who went on to run marketing and media services at BBDO, then Chairman of the international division of Bates, then global CMO for McDonald’s. And Lew Pringle, who went on to found and run marketing sciences for BBDO, then Chairman of BBDO Europe. The mid-sixties were abuzz with flux and transition for marketing research, a period when the field became much more deeply grounded in the newly emerging discipline of marketing science. Kevin, Larry and Lew were part of the close-knit community of researchers who were inventing and expanding the application of sophisticated modeling techniques, largely borrowed from operations research (OR), to the analysis of increasingly rich and detailed purchasing and media data using computing power newly accessible via time-sharing systems (and later, micro-computers).

Kevin believed unequivocally in the power of quantitative analysis. In his 1991 manifesto, The Marketing Revolution (HarperBusiness), Kevin had this to say about qualitative research: “The most popular form of preposterous research is the ubiquitous focus group.” Kevin minced no words. He added, “Yet companies love a good group, particularly if it’s done in an interesting place.” For Kevin, research should be optimization—you can hear OR echoing in his thinking. Companies are spending money, the goal of which is to maximize returns, period, end of story. This, then, is the job of research—optimizing marketing, which inherently makes research a quantitative discipline. Anything else from research, in Kevin’s view, is ‘preposterous.’ And actually perilous.

To get this message out to a bigger audience, Yankelovich ran a 1990 ad campaign that was a fancy version of a slide Kevin used to present (with a grin). It pictured a tombstone beneath the headline, “Every 7 minutes another marketing plan dies,” with the epitaph, “Here lies another ill-fated marketing plan.” The victim, one can assume, of preposterous research.

But Kevin wasn’t merely preaching optimization. He was very clear about what to optimize—profitability. Not survey metrics of what consumers think, believe, want or would buy. Or at least not such metrics apart from profitability. Nowadays, some measure of financial value is almost always built into segmentation and targeting. But not then. Kevin was channeling OR and marketing science into better research.

Mind you, it wasn’t that Kevin saw no role for qualitative or purely descriptive segmentation. Rather, he felt what consumers said had to be calibrated not taken literally. And he believed strongly that stopping with qual and making decisions just from that kind of information was a sure path to failure. True marketing intelligence required quantitative modeling, and Kevin had a tried-and-true way of making this point, one that always got people lining up after every conference speech.

Death Wish Marketing. This was Kevin’s favorite phrase for marketing decisions made with poor rigor, bad data and/or no science. Which made him no fan of brand managers. Too often, he had watched marketers rely on gut instinct to make critical and costly decisions. Which generally ended in failure. Kevin’s favorite way to open a presentation about how to do research or why to work with Yankelovich (or his later firm, Copernicus) was to cite the apocryphal stats on marketing failure rates (from two-thirds to 90 percent). In other words, marketing almost always fails. Then Kevin would tell you why.

Make it simple, he would say. Twelve decisions in a marketing plan—target, positioning, ad execution, product and packaging, pricing, distribution, media spend, media mix, media schedule, promotion spend, promotion mix and promotion schedule. Even simpler, assume there are only seven choices per decision (although in reality there are always many more). That means the number of potential marketing plans is 7 to the 12th power, or 13.841 billion possibilities. Gut instinct is a one in 13.841 billion bet. I.e., death wish marketing.

Kevin’s point was that the odds are well against making the correct decision in the absence of quantitatively-based decision-making. Or as Kevin liked to put it, “There are many roads to disaster. Only a few to the Emerald City.” Picking one without first using rigorous modeling and simulation methods to iterate through all alternatives is almost certain to be a bad decision. Death wish marketing is the inevitable product of death wish research.

The problem stems from marketers being too sure of themselves. It’s a job that attracts strong, confident personalities, but that mettle needs to be tempered. Kevin used to joke that brand managers have a high testosterone to IQ ratio. Kevin was all in favor of nerve and pluck. He just wanted that to be guided by smarter thinking.

Kevin doubled down on this point by recasting common marketing rules-of-thumb as myths. “The most appealing product is always the least profitable.” “You don’t need to deliver perfect products.” “If your prices aren’t based on strategy or research, you must be clairvoyant.” From this small selection of Kevin-isms, you get a sense of how he thought of marketing intelligence, the absence of which means death wish marketing.

The Strategic Cube. The most important thing I learned from Kevin was the necessity of bringing a model to data analysis. That is, always have a structure to organize and interpret your findings, one that leads automatically to a specific decision. Never post tables or run analyses willy-nilly, and certainly never sort through data haphazardly looking for patterns or something, anything interesting to report.

The Strategic Cube was a model for identifying the optimal brand positioning. Which embodied a theory about what constituted an optimal positioning, derived from prior research into what worked best in the marketplace. It was also a model that told you exactly what you needed to research, how to pull everything together, and how to interpret the results to make a decision. In short, a blueprint for action. The Strategic Cube is straightforward. The best theories always are. Three things combine for an optimal positioning—a highly motivating attribute or benefit (whether tangible or intangible) that is credible for your brand and preemptible versus the competition. Every attribute and benefit of a brand can be plotted within the model, and each cell of the blueprint corresponds to a specific implication or decision.

When we think of models, we often envision gobs of equations and millions of Monte Carlos. Those are models, but there are many kinds. Most are simple. A model is just a way to organize data that structures thinking and points to a decision. Kevin believed in the power of models, both complex and simple. Both types organize data and structure thinking for better decision-making. As Kevin put it in the title to another book, Your Gut is Still Not Smarter Than Your Head (Wiley: 2007). As long as you are using a model to make yourself smarter, that is.

Every time Kevin tackled a new area of marketing, he would develop a model for turning data into decisions. He did this for segmentation, for pricing, for forecasting, for tracking, and for the corporate reputation system he developed, with help from others at Yankelovich, for Fortune.

Building a forecasting model is how Kevin ended up running Yankelovich. He’d been hired as a consultant to modernize YSW’s forecasting system, which he did. But YSW decided not to implement it. So, YSW’s Robert Shulman left to partner with Kevin and start a new firm that was all-in on ‘state-of-the-science modeling.’ Soon thereafter, it was bought by Saatchi; then, ironically, merged with YSW, another Saatchi business.

Throughout much of his commercial career, Kevin was also on the faculty at Boston University. Kevin’s salad days were the heyday of close ties between academics and practitioners, who working in concert to develop the new science of marketing. A few, like Kevin, straddled both, which made Kevin particularly attuned to the need for applied science. Those are the kinds of models he favored.

Of course, for many, the idea of models conjures up the dirtiest word in custom research—product. But Kevin’s models weren’t mere products to peddle. They were the structured embodiment of theories and ideas about optimal marketing. Ideas were what I sold at Yankelovich. Sure, they were Kevin’s ideas, but in my opinion, they were, and by and large still are, the best ideas out there. I wanted to sell them. I got to traffic in ideas. Theories of marketing. Concepts about doing research. Viewpoints about what makes ads and brands work. All in the form of models for making those decisions correctly; indeed, optimally.

RIP, Kevin. It was a heady time, those days. I was hired to open an office in Atlanta. A year later, a deal by Saatchi to sell Yankelovich to private equity firm Wand Partners meant that my time working with Kevin was brief. But Kevin has continued to inspire me ever since. As well as many others. I am forever indebted. Thank you and godspeed, Dr. Clancy.

Contributed to Branding Strategy Insider By: Walker Smith, Chief Knowledge Officer, Brand & Marketing at Kantar

The Blake Project Can Help: Discover Your Competitive Advantage With Brand Equity Measurement

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Growth and Brand Education