The modern Mini Cooper—offered in a variety of eye-popping colors—burst onto the scene in 2001 as a chic version of an old British classic. It quickly became a fixture in trendy urban neighborhoods around the globe. Today, nearly twenty years later, the car still hasn’t lost its freshness: demand for Minis has remained robust with annual sales increasing at a steady pace of 5.2% per year.

On paper, the Mini doesn’t look like it should be such a break-out success. While its modest size makes it ideal for city living, other cars such as the Honda Fit or the Chevy Sonic are equally manageable in tight quarters. The Mini’s Comfort ratings in the Kelley Blue Book are tied with those of the VW Beetle and Toyota Yaris. Its gas mileage is no better than its competitors’, and sometimes it is worse. And with a sticker price that averages about $5,000 more than comparably sized rivals, the case for buying a Mini seems pretty weak.

The Mini’s surprising success comes from its unique, almost ineffable customer appeal. People just feel good about buying one. Its distinctive sporty shape, for example, allows owners to stand out from the pack. The option of a convertible top adds an extra element of cool. The Mini colors and add-ons are also atypical and can be used as an expression of personality. A shocking yellow Cooper with racing stripes tells the world that you are audacious and fun; a dark purple Roadster signals stylish sophistication; a chocolate brown Countryman is for those who like to travel the unbeaten path.

By recasting a car purchase as a bold act of individual expression, Mini has ensured that it will remain competitive in the small car market both now and well into the future.

Figuring Out Emotions

As the appeal of the Mini shows, people are not rational decision makers. Our feelings and emotions influence our choices more than our most logical justifications. We rarely articulate these emotions clearly, and even when we do, we may not openly acknowledge just how important they are. But these emotions are at the very center of our decisions. Digging deep to uncover both the emotional and practical factors behind a purchase decision allows us to more accurately predict whether a new proposition will succeed.

There is no doubt that emotions are notoriously tricky to pin down. Unlike variables such as cost, size, or ease of purchase, emotions are neither discrete nor concrete, making them difficult to compare. What “delights” one consumer may “thrill” another. The question is, what’s the difference? And does the difference matter?

So what’s the solution? We have found success understanding customer emotions using a Jobs to be Done framework which builds on the work of the late Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen. Rather than trying to measure specific emotional reactions, we focus on identifying the emotional jobs that consumers want to get done.

Unlike emotion, which is a sentimental response to an outside stimulus, an emotional job is a specific emotion-linked task that the customer is trying to accomplish by purchasing or using a product or service within a defined context. Emotional jobs are robust because they address root motivations and emerge as a result of clear attitudinal or circumstantial factors.

For example, understanding that a car makes a customer feel special can hardly be called an insight. “Feeling special” is too vague an emotion to be meaningful. Recognizing, however, that for one customer, “feeling special” means addressing his emotional job of “standing out from the crowd” within the context of a “being a hipster who recently moved to the suburbs” opens up whole new areas for action. The emotional job serves as a sort of compass; it lays out pathways for creating targeted, meaningful, and relevant innovations.

Quantifying Emotional Jobs

Measuring emotions with a quantitative survey is difficult, but there is a way to do it. Our research into emotional jobs is guided by three key principles:

Principle 1: Quality Before Quantity

It’s tempting to try to explore all possible jobs when fielding a survey. No one wants to risk missing an important insight because they forgot to ask. But while stuffing a survey full of questions is a bad idea in general, it’s exponentially terrible when emotions are involved. Asking about too many emotional jobs at once will fatigue the respondent and decrease the reliability of their responses.

What to do? We’ve found that the best way to narrow down your questions to a more realistic list is two-fold:

- Conduct qualitative research before you design the survey. This way, you can push respondents to generate their own lists of high-priority jobs instead of giving them a list of possibilities based only on your initial assumptions

- Ask about emotional factors in an open-ended way. If customers use nebulous terms like “gratifying” or “trust,” ask them to define what they mean. This way, you can drill down this feedback into a concise list of factors that can be tested and measured

Principle 2: Seek A Hierarchy Of Emotions

Functional jobs to be done are often relatively obvious and easy to arrange into a clear hierarchy. Not so with emotional jobs. Emotional jobs are often related in complex ways, and they can heavily influenced by contextual factors, making it difficult to understand how to sort and compare them. If emotional jobs and their relative priority become jumbled, you risk targeting the wrong emotion.

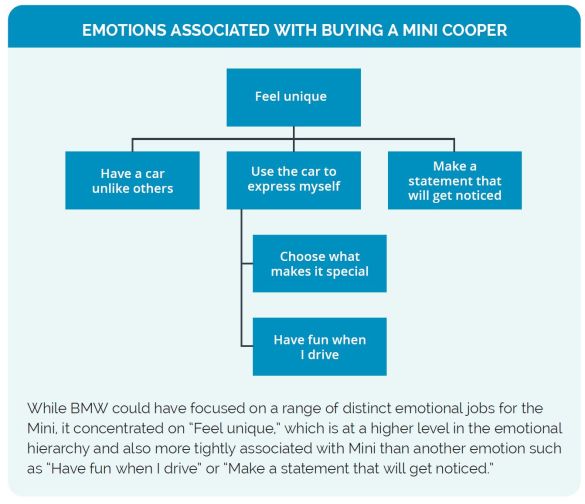

For example, the Mini is cool and stylish, but those factors are less important than its uniqueness – its target customer prizes uniqueness first, rather than those who might wish for a stylish but more conformist vehicle. Style supports uniqueness in this case, but it does not supersede it. Fiat owners, by contrast, may have the reverse set of priorities.

To get these insights via a survey, ask respondents to weigh their priorities against each other, rather than having them simply assign numerical ratings of importance. Is it more important, for example, to be unique or stylish? This is a more realistic question than one that would force people to put a number on, say, the value of uniqueness. Then, you can pit prioritized emotions against functional benefits. Is it more important to be unique or to have great gas mileage? In this way you get to useable data which is both accurate and tractable.

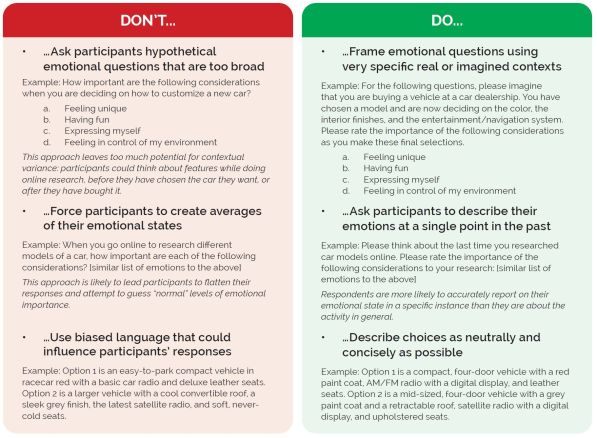

Principle 3: Context Is Key

Emotions are highly context-dependent. The desire for uniqueness, for instance, can manifest differently to a new parent who feels forced into routines, or for a middle-aged professional yearning to rebel. Sometimes an emotion will not be present at all until it is triggered by an event or other contextual change. If survey-takers respond based on different imagined contexts, their answers can be highly divergent.

Control for this variability by describing in detail the contexts in which you’re asking them to imagine themselves. You can also ask about a specific instance when they used or purchased your product or service type. Think about it: do you remember more clearly why you bought your last cup of coffee, or why you purchase coffee on average? When answering about a recent, concrete instance, respondents are more likely to remember their choices and feelings accurately. Of course, make sure to capture what that context is either through providing it or supplying a handful of choices.

Emotions can sometimes be best understood in relation to the choices they motivate. If you were assessing what leads people to chose one doctor over another, for instance, you could describe two hypothetical physicians succinctly, ask respondents to choose one, and then have them rate the importance of various emotions in that decision. In this way, you can normalize answers to a clear context and enable respondents to compare emotional jobs that may be in tension with each other, such as a having rapport with a physician or feeling assured about medical expertise. Then you can change the contexts and see how the roles of these factors differ.

Putting It Together

Following these principles generates many benefits:

- Emotions are framed in ways that resonate with customers

- Emotions are disaggregated into more manageable components that can be targeted through product, service, and marketing

- You get an accurate sense of how important emotions are relative to functional jobs, and therefore how much to invest in achieving each type of benefit

- You can link together complex emotions in simple ways, anchoring your value proposition in a way that is simultaneously evocative and straightforward

Emotions need not be opaque, and quantitative analysis of them need not be imprecise. When you approach emotional jobs with intention, you can discern their importance clearly, just as BMW did when it first introduced its hip, customizable little car.

Contributed to Branding Strategy Insider by: Steve Wunker and Jennifer Law. You can find much more on these concepts in their new book Costovation.

The Blake Project Can Help You Grow: The Brand Growth Strategy Workshop

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Growth and Brand Education