Long ago and far away, I started my career at General Electric. It was the early 1960s and, in hindsight, it was a wonderful time. Competition, as we know it, just didn’t exist.

GE’s main full-line competitor was a company called Westinghouse, but by today’s standards, it was barely a real one. Westinghouse was a player, but GE actually saw the company more as a necessity. If that competition ever went away, the government would pounce on GE to break its hold on “electricity.”

Back then, nobody really worried much about mistakes because CEOs figured they would be able to get any lost business back in the end. (Jack Welch hadn’t yet arrived at GE. After he took over, everyone worried a lot more about mistakes.)

What’s Changed

Today there are so many competitors that they quickly take your business if you make a mistake. Your chances of getting it back are slim unless someone else in turn makes a mistake. Hoping for competitors to make mistakes is like running a race with the hope that other racers will fall down. It isn’t a very smart strategy.

Even worse is the large number of participants in each race. Every category is haunted by what I call the “tyranny of choice.” Consumers have so many choices that one false step brings not just one, but an army of competitors to take advantage of your misstep. And what’s especially tragic is that you don’t get that business back. It’s gone. Does General Motors come to mind?

Now let’s take a look at some of the most prevalent blunders in our hypercompetitive world and hint at the lessons they provide.

The “Me-too” Mistake

Many people believe that the basic issue in marketing is convincing the prospect that they have a better product or service. They say to themselves, “We might not be first but we’re going to be better.”

That may be true, but if you’re late into a market space and have to do battle with large, well-established competitors, then your marketing strategy is probably faulty. Me-too just won’t cut it.

A major disadvantage of being a me-too is that the name of the first brand to market often becomes generic. Xerox, Kleenex, Coke, Scotch tape, Gore-Tex, Krazy Glue, and Q,tips all have an enormous advantage over competitive me-too products.

If the secret of success is getting into the prospective customer’s mind first, which strategy are most companies committed to? The better-product strategy. Benchmarking is a popular subject in the business management field. Touted as the “ultimate competitive strategy,” it involves comparing and evaluating your company’s products against the best in the industry. It’s an essential element in a process often called “total quality management” (TQM).

Benchmarking doesn’t work because regardless of a product’s objective quality, people perceive the first brand to enter their mind as superior. When you’re a me-too, you’re a second-class citizen. Marketing is a battle of perceptions, not products.

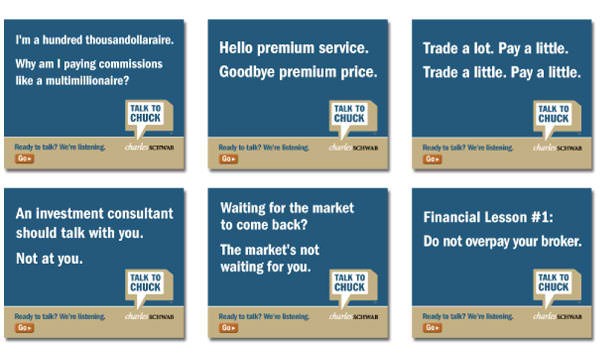

When you enter a market, a far better strategy is “Differentiation.” Why are you different from the other players in the category? If you can define that difference in a meaningful way, you can escape the me-too trap. (How to do this is outlined in my book, Differentiate or Die)

The “What are you Selling?” Mistake

This may surprise you, but I have spent a good bit of my time over the years figuring out exactly what people are trying to sell. Defining the product category in a simple, understandable way is essential.

Companies, large and small, often have a tough time describing their product, especially if it’s a new category and a new technology. Or else they describe the product in confusing terms that doom the effort right out of the gate.

The positioning of a product in the mind must begin with what the product is. We sort and store information by category. If you present a prospect with a confusing category, your chances of getting into his or her mind are slim to none.

What’s a PDA.?

Consider the problems that Apple encountered with the introduction of their Newton, a product they called a “PDA.”

Immediately, their biggest positioning problem was: What are we selling? The first print advertisements asked the question, “What is a Newton?” The television commercials asked the questions “What is a Newton? Where is a Newton? Who is a Newton?”

Apple, however, failed to answer these questions with words that users could comfortably absorb.

PDA, or “personal digital assistant,” is not a category, nor is there much hope in its becoming one. (Pretty Damned Abstract is one tongue-in-cheek definition of PDA.)

Companies don’t create categories. Users do. And so far, users haven’t turned PDA into a category. Have you heard anyone ask another person about his or her PDA? It sounds like a medical problem. Even the trade press has landed on “Hand helds” as a generic term.

And you can’t force the issue. Customers either are going to use your words or they aren’t. If they don’t, you have to give up and look for a new category name.

The Newton died, and the Palm…

The Blake Project Can Help: The Brand Positioning Workshop

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Licensing and Brand Education