Whether the role of brands in people’s lives is for the better or for the worse is a long-running debate. The most influential anti-brand voice of recent vintage is journalist and social provocateur Naomi Klein, who shot to fame on the cusp of the new century with her bestseller, No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies, in which she denounced global brands for distorting markets, culture, work and even consumerism itself.

A contrary position defending big business in general, not just brands specifically, was articulated by George Mason University economist and popular blogger Tyler Cowen in his 2019 book, Big Business: A Love Letter to an American Anti-Hero. Cowen argued that the virtues of big business are so deeply taken for granted that it can be hard to bring them into clear focus, one of which is the fundamental fact that brands are the producers of the prosperity we enjoy and consume. (And as a fun finishing touch, in the final footnotes to his last chapter, Cowen cited some social science he termed speculative that purports to show people behave better after exposure to brands like Apple and Disney.)

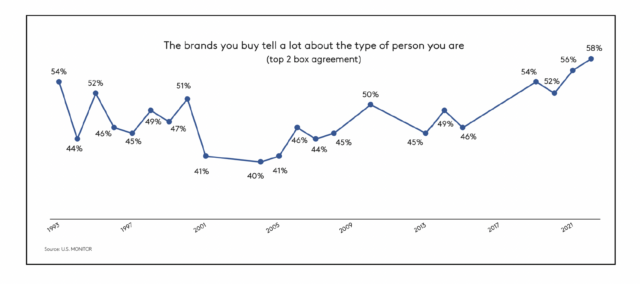

Pro or con, the assumption running through this debate is that people are closely connected to brands, perhaps even identifying with them. But this, too, is debatable, with many arguing that branding is not as central to buying as claimed or that branding works more by catching the eye than by stirring the heart. So, the question of connection is important to examine. U.S. MONITOR offers some useful perspective. The type of person that I am. Off and on since 1993, MONITOR has asked a question about agreement or disagreement with the statement, “The brands you buy tell a lot about the type of person you are.” This is a question about how much people feel that brands reveal their identity. Agreement might imply that people choose brands to make a statement about themselves. But even if not an intentional signal, agreement at least means that brands are a clue that others can rely on.

Obviously, this question is not a definitive or full measure of the roles that brands play in people’s lives. But it is a question worded to directly zero in on brands in a strongly stated way. We know from experience that strong, direct questions provide better discrimination and insights by pushing people away from both yay-saying and hedging.

Here’s what we see as we have tracked this question over time:

An Elbow Up. Correctly interpreting trend lines can be tricky, and this one is not completely straightforward. So, let me step through it. And don’t worry, what follows is not nerdy research talk. As can be seen in this trendline, more often than not, the majority of consumers have disagreed with this strong statement about brand identity. In the twenty-some years from 1993 to 2015, half or more agreed only four times. Usually, it was less than half, often much less.

Over this period, each of the highs was preceded (except for the first) and followed by much lower agreement, so it was a pattern of random wobble around a flat line. There does seem to be a drop-off right after the turn of the century, but soon it returned to the previous level. It’s the last four years that have broken the pattern—it’s more than half in each year, with the look of an upward trend emerging, though way too soon to tell. But even if agreement is not trending up, it is still noticeably higher than before.

That said, we should keep in mind the actual levels we see here. While the most recent reading of 58 percent is the highest ever, the 42 percent who disagree is as high as the typical level of agreement during that two-decade run from 1993 to 2015. There is no consensus view on this question—not before, not now. Brands are self-expressive for many, but far from all, even with the recent uptick. So, takeaways should be drawn with caution and no over-generalization.

The Product Era. The formative era of modern advertising was product-centric. The ‘Mad Men’ TV show was basically a historical fiction of the ad industry in the 1960s at the tail end of that era (albeit with drinking and womanizing amped up for dramatic effect). It revolved around the character of Don Draper, whose style and thinking were meant to epitomize the creative philosophies of seminal mid-century ad figures. Like Albert Lasker (1880-1952), who invented the job of copywriter, and Rosser Reeves (1910-1984), who invented the USP or the idea of the unique selling proposition. Lasker said copywriters had one job—to write about the product. Reeves told them what and how to write about it. The product was king as the modern consumer economy took shape during the tumultuous first half of the 20th century. But the 1960s were more than one last ride on the Mad Men merry-go-round. This decade also ushered in a new way of thinking about advertising.

The Era Of The Person. In the aftermath of WW2, philosophers, writers, scientists, artists, musicians, historians, economists, and other public intellectuals, including media theorists and management consultants, all contributed to an intense, communal soul-searching and rethinking of society, culture, politics, and business. Broadly speaking, there was a turning away from traditional institutions—including everything from monarchies and colonial empires to political parties, church, government, and business. This unleashed an explosion of new cultural forms that celebrated individualism and self-expression. Advertising was caught up in this no less than anything else.

Primary emphasis on the product gave way to a new emphasis on the individual person buying the product, the most famous example of which was the Pepsi Generation campaign that debuted in 1963 and helped kick off the advertising Creative Revolution that is no less influential today. The people who bought a product were the selling point of a brand. Buying it would signal to other people that you are that type of person. Not a brand as the best product, but a brand as the best way to represent oneself to others.

So, how has this played out, then and now, in terms of expectations about brands? How much of this do consumers want from brands? Brand as self, sort of. Boomers grew up during the 1960s and 1970s period of newly permissive self-expression, and thus, we might expect to see a lasting impact on their attitudes about brands as a means of self-expression.

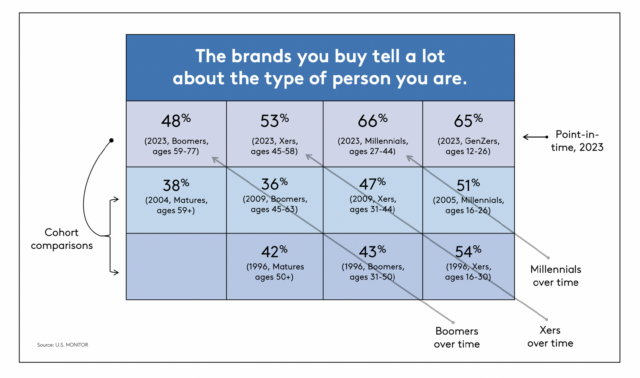

We can look at them in contrast to other generations in the table below.

Apologies for this busy table, but it’s the most efficient way to show the three relevant comparisons: Point-in-time. Over time. Cohorts.

The point-in-time comparisons across the top row show Boomers lowest, the younger cohorts highest, and Xers in-between. It looks like something to do with being young, but that doesn’t answer our question about Boomers, and it raises more questions about the other cohorts.

We need to dig deeper. Which means I’m going to have to geek out for a few short paragraphs. Hang tight. This won’t hurt for long. Look at the diagonals, which show each cohort over time. If there is a youth effect, we should see higher agreement within each cohort at younger ages. But there is no change, except for Millennials, and that bump is in the wrong direction for a youth effect.

It’s more nuanced, though. Boomers and Xers did go down slightly (diagonally, row two vs. row three), then, like Millennials, jumped up a bit (diagonally, row one vs. row two). Some societal factor might be the reason for this recent increase in agreement, but it affected all cohorts similarly, not differently, according to age. This raises the possibility that the point-in-time differences are cohort effects arising from generational starting points. To assess this, look at the columns stacking up cohorts at (roughly) the same ages. Scan them both up and down and sideways.

Admittedly, this is a lot of comparisons to take in all at once. But the overall pattern is what’s important. Sideways, at every age and in every comparison, Boomers tend to be lower, Xers slightly higher, Millennials higher still, and Gen Zers highest of all. These are cohort effects—persistent, consistent differences among cohorts. Up and down, the cohort effects only pop in recent years, suggesting an amplifying factor that affects everyone, yet to different degrees across the cohorts.

That’s it for the data torture. My hidden agenda was to show how I think through data. More importantly, three takeaways.

1. Brands are on the hot seat. It’s not just politics that have brands under the microscope. We are in an era of more demanding consumers—as my colleague Don Abraham puts it, confrontational consumerism. This is the societal amplifying factor I mentioned. Everybody expects more of brands than ever before. Plus, in a time when other institutions have lost ground, a bigger role is expected of brands, especially for the generations coming of age during this time. With more of their expectations invested in brands, younger people want brands to be better representations of themselves. Not as fashion; rather, as statements of identity and values. In no small way, this is politics, both left and right, through a side door. There’s no youth effect, but there is an effect on youth today that was not so for Boomers in their youth. It’s two-thirds of tomorrow’s consumers, a level of agreement unlikely to diminish as they get older, if the data tabled here are any guide.

2. Change happens on a long trajectory. The value shifts from over half a century ago are more fully expressed in tomorrow’s generation than in the generation of Boomers who grew up during that time. What we see here is a reminder that really big changes unfold generationally not just contemporaneously, and often with more impact as time goes by.

3. Don’t neglect performance and quality. Brands must deliver the solution(s) they are built for. Whatever brands may ‘tell’ about the types of people who buy them, they must work well. That may not be enough for many, but it’s more than enough for almost as many others.

Contributed to Branding Strategy Insider By: Walker Smith, Chief Knowledge Officer, Brand & Marketing at Kantar

At The Blake Project, we help clients from around the world, in all stages of development, define and articulate what makes them competitive and valuable. We help accelerate growth through strategy workshops and extended engagements. Please email us to learn how we can help you compete differently.

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Growth and Brand Education