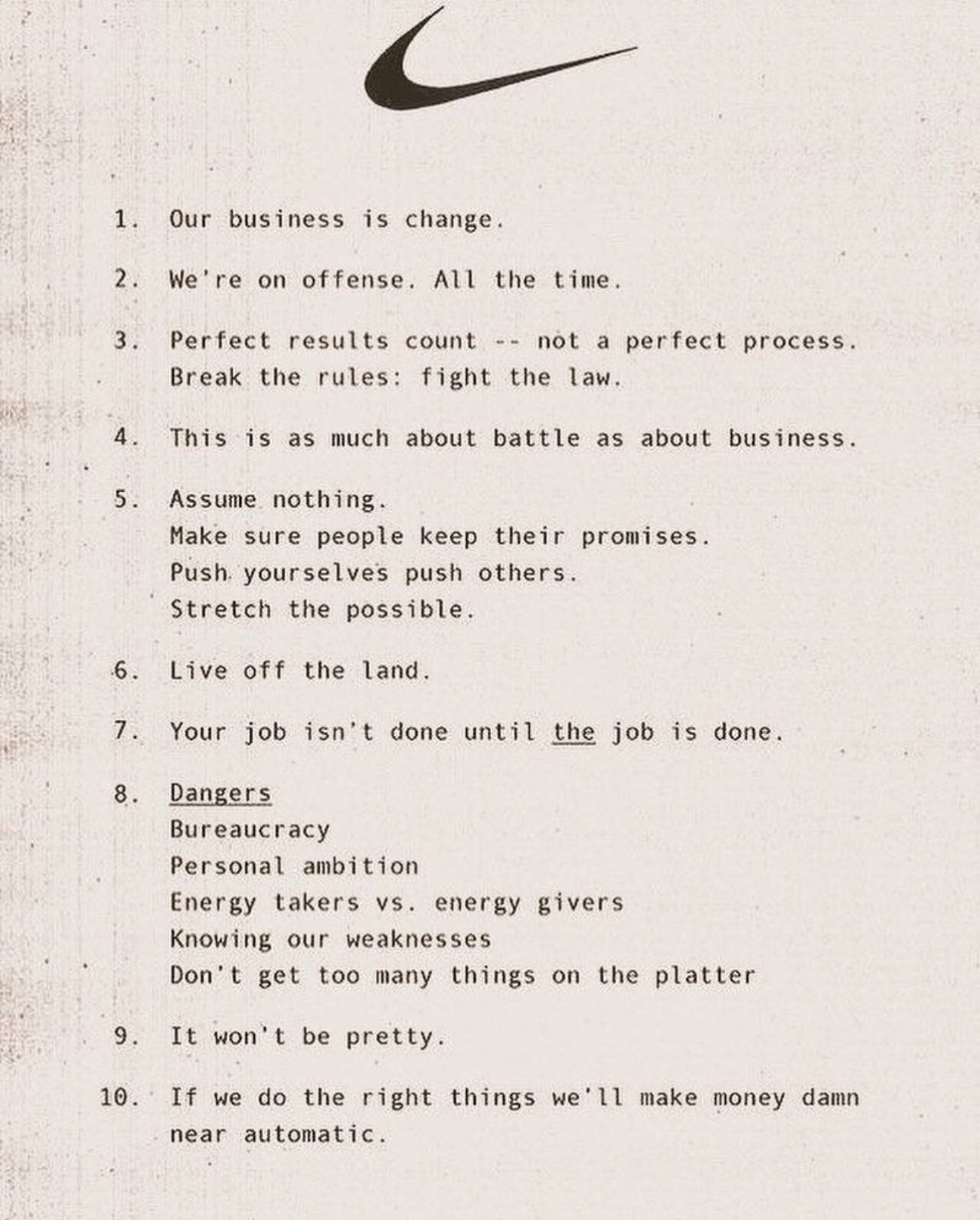

When Nike’s ten business development principles were written by Rob Strasser in 1977 the words marketing, systems, research and planning were all dirty words inside of Nike’s culture.

I know, I was there at this critical time in Nike’s growth. During those days Nike had very idiosyncratic, gruff, but brilliant leaders, who even though were grounded professionally on law (Rob Strasser) or accounting (Phil Knight) they used their native instincts and intuition over half the time. There was no paralysis through over analysis, there was always a bias for action. The mantra was to try lots of things, lots of new design concepts and marketing approaches, note what worked and get better over time.

If you really want to understand Rob Strasser and a half dozen other extraordinary and quirky leaders and geniuses of that time you’d have to read the book written by Rob Strasser’s wife, Julie, Swoosh: Unauthorized Story of Nike and the Men Who Played There. There have been many books written about Nike, this captures these wild go go years. The company was living off the land and its own street smarts. There were no firm rules. It was making up its own rules as it went along, based upon trial and error, stimulus and response, trying shit out, throwing product up against the retail wall and seeing what stuck versus what fell down. The early product and sales teams inside Nike were (in accordance with a Phil Knight principle) always moving forward, learning, making lots of mistakes, but never making the same mistake twice.

This ethos and management style is reflected perfectly in the simple one page memo below. It resulted in streaks of brilliance, like the signing of Michael Jordan. But, this style of management also had issues.

The coordination, communication and alignment of vast organizational resources (R&D, Advanced Materials, Product Design, Production, Sales, Distribution, Marketing: which consisted of product line management, athlete promotions, event promotions, retail promotions, product advertising, (and non-existent at this time); brand advertising, consumer research, product line marketing planning … all of the above can collectively be referred to as the Matrix Organization. Most of the division heads of all these areas were poorly communicating and coordinating with each other. They pursued sub-unit goals, not common external goals.

So when Rob Strasser left Nike, he left a big leadership void, but he also opened the door for new people, new thinking and new ways of working. Perhaps this is the hardest thing to see when you are living and working in a well defined culture with known motives and methods of work.

While I was there observing how things got done under Strasser as VP of Marketing, I was also observing what Strasser and his team weren’t doing. And when Strasser left, I saw a window of opportunity open up. So, I called for a meeting with Mark Parker (at that time head of Nike footwear Design, now Chairman of Nike) and Tom Clarke then just leaving as head of Nikes Sports Research Lab, on his way to take over Strasser’s job as VP Marketing. Seven years later Tom became CEO of Nike and held that position for another seven years.

At the time, I was a financial systems analyst working for Nike’s controller, and just completing a two year project to redesign Nike’s core financial systems, upgrade our chart of accounts, and consolidate 52 sets of accounting books into one integrated management reporting system.

I had interviewed every department manager on their budget and operational reporting needs, and I was surprised to find that Nike didn’t have a true marketing department, had never written a marketing plan, and didn’t have feedback systems to help gauge the effectiveness of product line management, advertising, or sports promotions. That is, in terms of learning what was working and what wasn’t in the marketing mix, we were flying blind.

The goal of the meeting with Parker and Clarke was to convince them that the company would benefit enormously by adding marketing planning, systems, and research to improve how business was being done. I had been warned that someone had recently tried to impose a more formal marketing planning system on the company, but after nine months he’d been ejected from the company like a virus, so it was with some trepidation that I approached Parker and Clarke to present my ideas on what had already proven to be a very unpopular topic.

I presented them with two maps, one tracing the process flow for bringing a new product to market and the major hand-off points between departments, the “status quo,” and on the other a process flow that included a simple marketing planning framework that could be owned by the product line managers, the goal of which was to increase strategic insight into how to make more effective business and brand development decisions.

The meeting went well; a week later I was offered a new job (without a title) working under Tom Clarke to quietly bring the new map to life, so in the spring of 1986 I transitioned from Financial Systems to become Nike’s first Director of Marketing Planning.

My tools were my education, my knowledge of Nike core systems, and an Apple Macintosh (the first in the company).

I had a clear mandate, but no grand announcements were made about my formal role, because any announcement about new systems, planning and research tools would have guaranteed cultural resistance and a quick failure. When people asked me what I did during my first year, I’d say, “I’m the product intelligence officer,” which was sufficiently ambiguous and mysterious enough to keep the naysayers away.

A Brand Culture Is Born

It helped me enormously that I wasn’t just an analytical geek who knew how Nike core systems, data flows, and decision points worked. I was also a runner, and every day at lunchtime a large contingent of management could be found in the locker room suiting up for their daily runs. I got to know all the senior managers as runners and people, and I befriended the running product line manager, Claire Hamill, and offered to help her develop the template for a marketing plan. We developed the first marketing plan for the footwear running product line. The fifteen-page document looked something like this:

Market Situation Analysis:

- US Running Category, Size and Growth Rate

- US Running Category, Market Shares (Leading Brands)

- Nike Sales and Market Share, Current Year & Projected Two Years Out

- Target Running Consumer Profiles & Segmentation (by product / pricing levels)

- Nike Running Product Line, by Season Projected Two Years Out

- Competitive Analysis (Brands, Key Products – How Nike was ahead, equal or behind)

- Channels of Distribution Analysis (Strengths & Weaknesses)

- Advertising & Communications Analysis

- Sports Promotions & Events Analysis

- Issues Analysis: SWOT Analysis (Internal Org Strengths & Weaknesses vs. External Threats & Opportunities.

Marketing Goals:

- Financial Goals: Current Year Plus Next Two Years (sales, units, margins)

- Brand Positioning Goals: What people believe now versus what we want people to believe about Nike’s running presence 2 – 5 years in the future.

Marketing Strategies:

- Product Line Plan (18 months to 2 years out)

- Products Linked to Consumer Segments, Product line story presented in Sales Toolkit

- Advertising Plan (Identification of statement products, athletes, stories and campaign concepts) … this info became the basis for new ad briefs.

- Promotions Plan (Athletes, Events, Camps, Clinics, etc.)

- Public Relations Plan (to augment advertising reach)

Consumer Research Plan

To eliminate key marketing blind spots.

Organization Plan

To develop new talent, skills, technical capabilities to succeed.

It was monumentally difficult to gather all this information, but since product line managers were expected to request a budget to help move sales in their category forward once each year, developing a holistic vision of how all the marketing mix elements could be aligned and focused to achieve the greatest synergy was essential. It was evident that there needed to be one person responsible for a category to pull together the organizational insight and learning.

In the process of writing the first plan, a manager had to interview the heads of other business functions to understand what they could and would support, and critical to our success in the intuitive Nike culture, in the process of conducting those interviews, consensus was being built before the plan was written.

After Claire and I had written the first plan, some of the intangible benefits of marketing planning started to become apparent, including the power of focusing elements across the entire matrix organization to achieve campaign impacts.

That first marketing plan was placed in a ring binder so that pages could be taken out and updated as new information arrived, while the second-year effort to write the plan took a fraction of the time. It did not create paralysis by analysis, but instead created a useful narrative that enabled shorthand communications between business functions to focus company resources on creating greater brand synergies and impact.

Next I called on Ron Hill, the basketball product line manager and showed him what we had done for running, and asked him if he wanted to try something similar for basketball. Ron could have refused, and that would have been the end of it, but he immediately grasped that he was competing for scarce organizational resources to grow his basketball category. He realized that if the running product line manager had a better story, a justified story explaining why she was asking for millions of dollars in marketing support money that she hadn’t asked for in the prior year, and that it was justified by the size of the market, Nike’s market share and growth rate, and all the other assets and resources that Claire had shown she was focusing on through the plan to achieve seasonal campaigns to grow sales, Ron immediately came to the conclusion he needed a marketing plan for basketball too.

In this way, all the other product line managers learned about the marketing plan template, and soon my phone was ringing. By the second year, all product line managers in the apparel division were writing similar plans, and by the third year I was traveling overseas to show country managers how to think about marketing planning too.

Marketing Becomes The Hero

Several interesting things happened after marketing plans had been written for all of the 12 footwear product lines. First, management noticed something different in the sales meetings. By virtue of the fact that they had gone through the effort to analyze, plan, imagine, strategize, organize, and lead the thinking behind the marketing development effort, they were much more informed, inspired and fluid during sales meetings.

Their arguments for Nike superiority became more clear, profound, and considered. They developed perspective on where the brand was going that had never existed before, and the materials they presented to the sales agents became more effective. The storytelling about marketing direction strategically built upon Nike’s brand strengths, it remedied competitive product weaknesses, blunted competitive brand threats, and provided far more detail in profiling new opportunities and explaining how those efforts would be supported in the calendar year ahead.

Prior to the advent of this new planning process, Nike was already a great organization. It had streaks of marketing genius, as the Air Jordan phenomenon clearly showed. But as Nike was rising in stature, the public couldn’t see the depth and breadth of all of its product lines. Product category management lacked synergy, coordination, and focus. Functional heads across the matrix organization pursued their own sub-unit goals, unconcerned about external team impacts.

Ultimately the new planning approach succeeded because it created a framework for analyzing the business more rigorously to justify increased investments in developing the business and brand further. It allowed the matrix organization to learn how to mesh to support campaign launch events, and the results of these changes were profound. In the ten years after the installation of annual marketing planning Nike grew more than 860% in annual sales, and the process of annual marketing planning was key to organizational learning from successes and failures.

It’s fair to say that today, as Nike surpasses $35 billion in annual sales, marketing and marketing planning are no longer dirty words, but a welcome way of life that has helped the company to achieve market dominance.

These and other insights into brand management is covered in greater detail in my book, Soulful Branding – Unlock the Hidden Energy In Your Company and Brand. For more about Nike, here’s what I learned working on the Just Do It campaign.

The Blake Project can help you make the shift. Please email us for more about our purpose, mission, vision and values and brand culture workshops.

Branding Strategy Insider is a service of The Blake Project: A strategic brand consultancy specializing in Brand Research, Brand Strategy, Brand Licensing and Brand Education